Why not?

The other day, a healthcare investor and I were discussing a new orthopedic technology. To set the stage, the investor is considering a substantial investment in the company. The company’s product is approved and on the market. Much of the risk of the deal is off the table…with the exception of the big one: market risk. All the work startups do from inception up to the eve of commercialization is necessary but not sufficient to guarantee success. Market risk is where the rubber meets the road.

In this situation, the investor is at a crossroads in the decision-making process. No doubt it’s a scenario with which you are familiar – large market opportunity, inadequate current options, easy procedure with no bridge-burning, CPT code in place. Slam dunk, right?

Not in this case. And not in many others either.

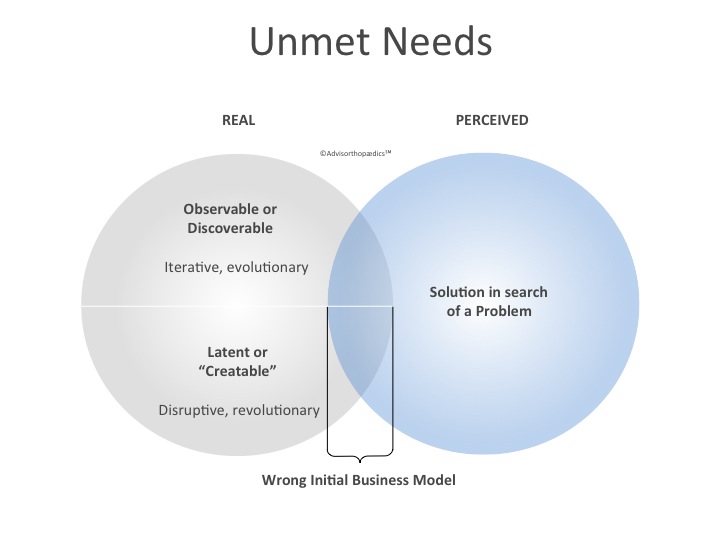

You’re familiar with the rest of the scenario too: the training of surgeons is exceeding forecast, but the actual procedures performed is failing to meet forecast. How do you reconcile this data with what seems, on the surface, to be so obvious? Is this just a good old fashioned growth equity play where well-timed capitalization will catalyze sales? Or is this a more fundamental failure to address a real unmet need in the appropriate context? Sometimes it can be very difficult to distinguish the difference, but I suspect it’s the latter in this and many other cases. “Real” and “perceived” unmet needs can look very similar, but have very different outcomes when a business model is applied. (Fig. 1)

As our conversation progressed, the investor explained all the reasons for the company’s potential success. Success in this case hinged on a crucial assumption regarding surgeon behavior. The investor said, “I mean, if it is simple to do and the surgeon can do concomitant procedures at the same time, make a little money doing it and preserve future treatment options, why not do it?”

Why not?

Seriously?

Although this was just a turn of phrase, it exposed the Achilles heel of this opportunity. “Why not?” is not an investment thesis. Put another way, if you feel the urge to shrug your shoulders as you justify your investment decision to others, you probably shouldn’t do the deal. Don’t misunderstand me. “Why not?” is a perfectly acceptable answer to a variety of questions. For instance, it’s fine to use it in response to the question, “Do you want fries with that?” “Why not?” implies triviality and lack of conviction. The choice is optional, the decision inconsequential. In contrast, deciding whether to intervene in any way in a patient’s clinical course is anything but trivial or inconsequential. And if the intervention is optional to boot, this “I can take it or leave it” product is not a game changer.

Can’t Hurt.

The fabled “Why Not” Principle of Investing would be analogous to a “Can’t Hurt” model of decision-making in clinical practice. Can you imagine what medicine would be like if all physicians were trained to prescribe something not on the basis of its anticipated therapeutic benefit but rather on the basis it has little chance of having a negative outcome? “First, do no harm” is our profession’s ethical standard, not “It’s ok if it doesn’t help as long as it doesn’t harm.” Nor is its corollary, “Can’t hurt, so might as well.” Physicians don’t practice the art of medicine this way. Neither should you, as an investor, practice your trade this way.

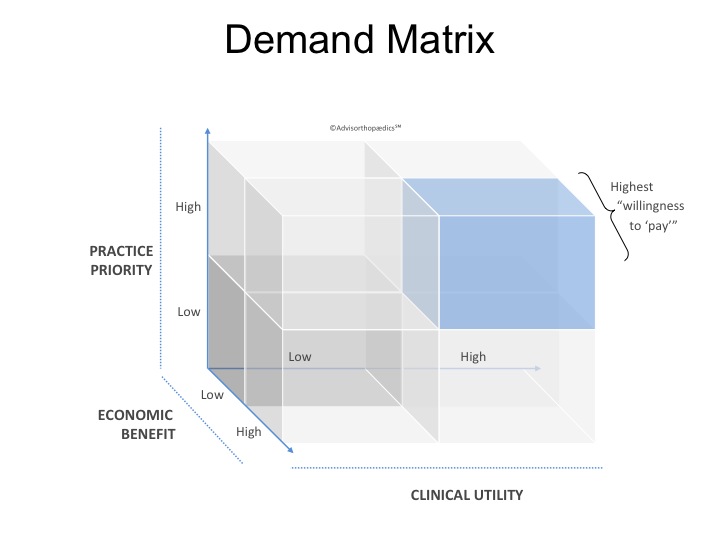

Acknowledging exceptions to the rule exist, physicians make treatment decisions based on what is best for patients in the context of their practice. From the outside, it might look easy and linear [e.g. cheaper product (A) + a better outcome (B) = immediate adoption 100% of the time (C)], but this decision-making is far more complex. When incorporating a new treatment into his or her practice, a physician weighs the cost-benefit analysis along both clinical and economic dimensions but adds a third dimension of which most investors aren’t aware (and, frankly, which most physicians can’t articulate): practice priority. In other words, where on the scale of significance does this problem fall relative to all the other clinical problems I address and how does addressing it with this product improve my role as a physician to all my patients, not just this one? I call it healthcare’s “Demand Matrix.” (Fig. 2) I have never seen this discussed anywhere – this is my own creation based on a lot of observation. But I believe it to be true.

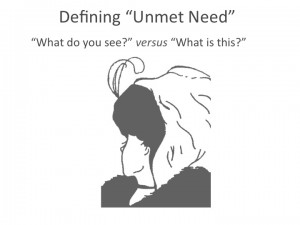

Physicians, surgeons in particular, are decisive and intentional. If you find yourself explaining away a lackluster adoption curve for a new product by blaming doctors’ behavior in order to justify an investment, then the answer is probably more obvious than you’re admitting to yourself. (Gary Larson succinctly illustrated this once.) It’s likely, at the beginning of the product development stage, the unmet need was misinterpreted or not clearly seen – it’s the difference between “what do you see?” and “what is this?” (Fig. 3)

What do I mean by that? We see the sun rise at dawn – that’s what we think we see anyway. It seems plausible too – all signals suggest we are standing still and the sun is moving. But that’s not what’s happening, is it? As the earth rotates around its axis, the sun’s image varies. Think how different your day would be if all the situations you encountered you placed in exactly the true and correct perspective. (Then again, think how little work you’d get done if you were constantly aware you were spinning at the rate of 1,000 miles an hour.) That’s certainly what you must do when you define an unmet need. It is a real exercise to do so, but making sure what you see is actually what’s happening is critical – this gets you started solving the real problem, not your interpretation of it. If not, the effort expended to develop a solution to meet your defined need risks being inappropriately focused and, as such, the demand for the ultimate product in the context of practice priority may not exist.

Just Because.

Can a product sell that doesn’t meet all the required thresholds in this matrix? Of course! That’s the “push” principle at work. It can and does work. Marketing is tremendously effective even in healthcare. It’s just that marketing a product which isn’t being “pulled” requires a lot more capital. Just because it can sell doesn’t mean it’s an optimal use of capital to sell it. “Because it’s there” and “because I can” are far less compelling (and sometimes more dangerous) motivations for doing something (often with less productive outcomes and less sustenance) than “because it’s needed.”

Many years ago, NBC’s Saturday Night Live did a brilliant faux commercial for Bad Idea Jeans in which the “just because,” “can’t hurt,” and “why not?” approaches to consequential decision-making were exposed. If you’ve never seen it, it’s a classic. I suspect all of us have worn a pair of those once or twice in our life. Periodically we may even be tempted to see if they still fit. Just because. I mean…why not? Might as well. Can’t hurt, can it? If you find yourself starting to slip into those jeans again by developing investment theses based on the “why not?” principle, stop. Step away from your “why not?” perspective and ask yourself instead, “Why?” Why is this product needed? Why would a physician be compelled to use this? Why does this make a difference? Why does this fit squarely in the “willingness to pay” part of the Demand Matrix? If the answers aren’t obvious, perhaps the wrong problem was being solved all along.

Leave A Comment